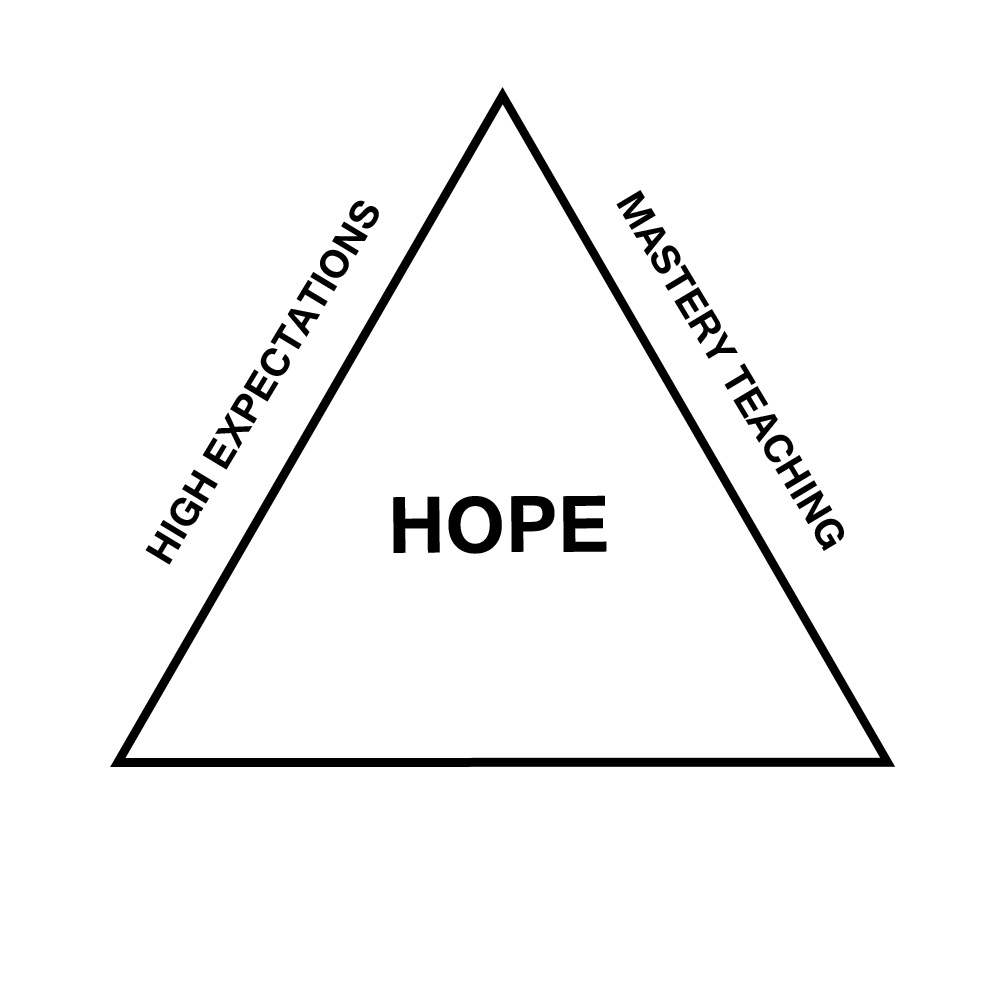

Last month we focused on creating high expectations. This month we’ll see how powerful it is to structure lessons to build mastery of skills and understanding of concepts. Sometimes taken for granted but also vital for students from poverty is the teaching of sequencing skills. All this leads to confidence and success to build upon: “I can do it!”

Last month we focused on creating high expectations. This month we’ll see how powerful it is to structure lessons to build mastery of skills and understanding of concepts. Sometimes taken for granted but also vital for students from poverty is the teaching of sequencing skills. All this leads to confidence and success to build upon: “I can do it!”

To begin these latest reflections, I want to say that I’m indebted to Dr. Fred Jones, whose outstanding book Tools for Teaching I’ve found useful for many years. I used it both at my school with the teachers and as nucleus of a course I created and taught for the University of Richmond in Virginia. Jones, a clinical psychologist, describes three “Fundamentals of the Learning Process”:

- All learning takes place one step at a time

- We learn by doing

- A picture is worth 1,000 words

Jones calls his teaching model “Say, See, Do” teaching. I prefer to call it mastery teaching. Briefly, the teacher models/demonstrates each step in the process. She teaches one step at a time in a series of input and output cycles. So after verbal/visual prompts or a demonstration for each step, students take some sort of action.

For example, long division in fifth grade is a very specific sequence of operations. “Here’s what we do to start. Watch me.” Students observe the step; the teacher says, “Now you do it.”

With this method the teacher has time to circulate and check each student’s work as he/she does the next step. Students don’t get hopelessly behind; they are focused only on the next step.

Learning by doing

This is learning by doing. Before it gets lost in short-term memory, do something with what you’ve just seen and heard.

And the teacher sees with her own eyes who “gets it” and who doesn’t. She doesn’t have to wait until the next day to check homework wherein those who didn’t understand have now practiced errors or started developing bad habits—or didn’t do the homework at all.

A positive aspect of teaching this way is how well it lends itself to partner teaching. In partner teaching each student in each pair sees and hears the same step three times (once from the teacher, once when he “teaches” the step to his partner, and a third time when his partner “teaches back” to him).

Such repetition is vital for students struggling with the process being taught. And the act of partnering has an added benefit since students from poverty in particular (Framework, pages 44, 67, 101) gain from the experience of give and take when working with another on academic pursuits.

The visual component is critical because everyone has a wonderful part of the brain called the visual cortex—a fantastic memory-storage mechanism. Contrast this with the auditory modality, which by contrast is a terrible facility for memory storage and access.

For example, would you do better if a stranger you asked for driving directions gave you a verbal description of the route you need—or a quick sketch of some sort? The choice is easy.

Most of us forget verbal directions almost immediately (short-term auditory memory is as short as two minutes in most people). Why is this so? Because what the brain mainly stores is patterns; that’s what the visual cortex is for. As Jones says, “You teach to the eyes, not the ears.”

Can you see why simply lecturing to students from poverty tends to be frustrating, even foolhardy?

Two other significant aspects of this approach involve corrective feedback and sequencing.

Corrective feedback

Think about it: If a student working independently during guided practice has a 10-step math problem (e.g., long division again) and gets stuck on the sixth step, is it helpful to show her the whole process, part of which she doesn’t understand? Or we can go back to where she understood the process (say step 4) and prompt her to do just the next step; just about anyone can do the next step.

During guided practice the teacher circulates around the room checking student work and returns to see that the student in question has successfully completed step 5 and is ready for step 6. This is also how Jones notes you wean the “helpless hand-raisers” from expecting you to reteach the whole lesson again because they are lost. You are building not only competence and confidence but responsibility.

Confidence is critical to fostering motivation; you’re building upon success, not focusing on what’s wrong. That is, when a teacher checks a student’s work during guided practice, typically she will say something like: “Let me see where you’re having trouble.” This is a negative, error-driven message that the child often translates to: “I can’t do it.” When he can’t do it, he may well give up.

That’s why going back and focusing on where the student was correct in the process—then correcting one step at a time—can be successful. The child does not give up; he has hope. He’s thinking, I can do this. Thus the path of corrective feedback is never harder than doing the next step correctly, having the teacher check that step, and the student gaining confidence and persistence.

But there’s another challenge …

Sequencing

Usually a big problem for students from poverty is sequencing. As Ruby Payne notes in A Framework for Understanding Poverty (pages 35–40), such children generally use random, episodic story patterns for memory recall. This tendency may be entertaining in a group setting, but it greatly hampers their ability to plan, which is critical to learning how to predict, how cause/effect relationships work, and how understanding consequences are related to controlling impulsivity.

Thus Jones’ approach to teaching step-by-step with corrective feedback is a big asset for developing the ability to experience cause/effect relationships and plan one’s efforts. And a huge help to planning and seeing relationships is using visual aids—what are commonly called graphic organizers. Most students from poverty need this type of structure to help focus their efforts. Remember the visual cortex? It captures images and patterns. In the chaotic world of poverty, this is a life jacket.

Thus Jones’ approach to teaching step-by-step with corrective feedback is a big asset for developing the ability to experience cause/effect relationships and plan one’s efforts. And a huge help to planning and seeing relationships is using visual aids—what are commonly called graphic organizers. Most students from poverty need this type of structure to help focus their efforts. Remember the visual cortex? It captures images and patterns. In the chaotic world of poverty, this is a life jacket.

We’ve all heard the question: “But what does this have to do with my life?” Making learning relevant is yet another challenge facing teachers. A huge issue is what Payne calls “hidden rules” (Framework, pages 43–59). The successful teacher of at-risk students must—at the same time—both honor the students’ backgrounds and hold aspirations that students will learn skills and behaviors (often hidden or unspoken) to be successful in the middle class.

As suggested above, many students are quick to say or think, “This isn’t about my life. Why should I care?” That’s why I have stressed the need to develop relationships of trust so students can begin to see where school and school ideas fit into a brighter future for them. In short, they are learning to defer gratification—an uncommon trait in poverty.

Why is getting what you need to succeed in middle class so important? Middle class is where commerce is conducted, people earn money, laws are made, people buy houses and cars, pay taxes, etc.—and students have to understand how their efforts (or lack thereof) impact their life. Not only do choices have consequences, but living in middle class means you are expected to take responsibility for what you do and don’t do.

How did we make our school relevant? In the elementary school, the choices of what students are reading (and as they learn to read) is a way to embrace students’ backgrounds while bridging to the choices life throws at all of us. Much of children’s literature is about choices and consequences; again, this is especially important to students from poverty.

I would add that having career days is important. In fact, just having adults/volunteers come to school to tutor or have lunch with the kids so they can see role models and make connections is powerful (more about this in my next blog).

Making the instruction connection

As discussed above, teaching students how to think (teaching routines) and ensuring they get the basics right (learning one step at a time) give all students a foundation of knowledge, skills, and experiences. They can then begin to see school as a place to succeed rather than fail.

And “Say, See, Do” teaching works particularly well in math and science, which are the heart of STEM (Science, Technology, English, and Math) learning. All this, taken together, shapes student motivation toward learning with an eye to the future. They have success to build upon and realize “It’s up to me.”

Early next month we’ll see what research (and our experience) showed was the critical factor in building motivation and effort.

Dave Burgess is an independent educational consultant in Richmond, Virginia. He is an adjunct professor for the University of Richmond and a university supervisor for James Madison University. Before retiring as a principal, he was a school counselor. He started his career as a teacher in public schools in Florida and Virginia. Dave can be reached at davidburgess789@gmail.com. The six-part series “A Path to Hope” began in January with the introductory blog “A Path to Hope: Critical Teacher Actions That Transformed a School.”