In the previous installment of “A Path to Hope,” we looked at the importance of strong teacher-student relationships. Today we’ll focus on discipline: the vital role of parents, how engagement supersedes misbehavior, and why out-of-school suspensions don’t work.

In the previous installment of “A Path to Hope,” we looked at the importance of strong teacher-student relationships. Today we’ll focus on discipline: the vital role of parents, how engagement supersedes misbehavior, and why out-of-school suspensions don’t work.

So what about discipline? As I noted in “Breaking the Cycle of Poverty,” the goal of discipline at my school was to teach responsibility and build relationships—not just stop bad behavior.

We really liked Fred Jones’ approach to management as outlined in “Breaking the Cycle of Poverty,” and we consistently applied his ideas. The main point of his approach is that you can’t control a roomful of students if you can’t first control yourself. Consistency is essential to effective discipline.

The key to motivation is engagement and respect. To restate what I said my previous blog post: “Simply put, motivation produces effort … effort produces learning … engaged learners are better behaved … students who experience respect learn to show respect.” You want engagement to supersede misbehavior. You can’t teach respect; you can only expect it, give it, and model it.

At our elementary school, we emphasized at every turn the importance of doing your best. I called students our Future Leaders. Our school culture was just that: Each child was valued and challenged. But discipline was an issue.

As the school principal, my job with discipline was not only to deal with issues, but always to get across: What would have been a better way to get what you wanted? How will you handle this type of situation next time? I expect you to learn from what happened and not repeat this behavior.

One thing I rarely did was out-of-school suspensions. Why? Three reasons:

- They don’t change behavior.

- They remove the student from a learning environment.

- They often kill home support for reasons you might not expect. For example, a working single parent must now have the child watched during the day; so the child was often sent to daycare or an elderly grandparent. There was minimal supervision and no sanctions for what got the child suspended. In fact, often the parent became angry at me and didn’t even address what caused the suspension in the first place.

Much more effective was in-school suspension/timeout in the room next to my office where the child sat at a desk part of the day or all day with work to do, had no interaction with the classroom or classmates, ate lunch there, and had to devise a plan.

The plan was for how he (or she) would behave when he returned, and it was discussed with the teacher and me. That is, breaking the rules was treated as a problem to be solved—by the student. It was his responsibility to fix it.

I worked very closely with the school counselor (and our general-resource teacher, who was my only other non-classroom support), along with our faculty to teach the students what Ruby Payne (A Framework for Understanding Poverty, 2013, p. 109) says is critical: Choices always have consequences.

Students who live in poverty seldom see this. To them, life is mostly unfair, unpredictable, and mean. Adults in their lives seldom explain their actions, and positive role models are hard to find.

School must be different from where one lives, and it starts with high expectations for every student, as well as fair consequences for one’s behavior choices. The long-term goal of building self-discipline goes hand in hand with learning to be responsible for your own choices—the good, the bad, the ugly.

Catch ’em doing well! Shorthand for this is positive behavioral interventions and support (PBIS). Our elementary school began this approach during the same year we first achieved state accreditation. The PBIS program proved beneficial to students in several ways because it:

- Shaped and reinforced the behaviors we wanted to occur

- Sent the message that hard work pays off

- Involved setting and pursuing goals

- Focused on improving behavior

Our school was chosen as a model for the state by the Virginia Department of Education. In fact, our core PBIS team gave presentations around the state and had many visits from school officials interested in what we were doing.

What about parent involvement? Adults living in poverty trying to raise children (often grandmothers acting in the mother role) usually have their hands full. For all the reasons outlined in Dr. Payne’s work (Framework, 2013, p. 99), involving themselves in their children’s schooling often is not a priority. This idea, of course, tends to offend the middle class, but it’s a fact of life.

So, what we did at my school was to involve and communicate with parents as much as we could. But the old truism often was the case: Those parents we most needed to interact with could not/would not come to school.

We knew the parents of our students loved them, but they were unaware in many cases as to how they could help. Most of them didn’t know the hidden rules of the worlds of school and middle class.

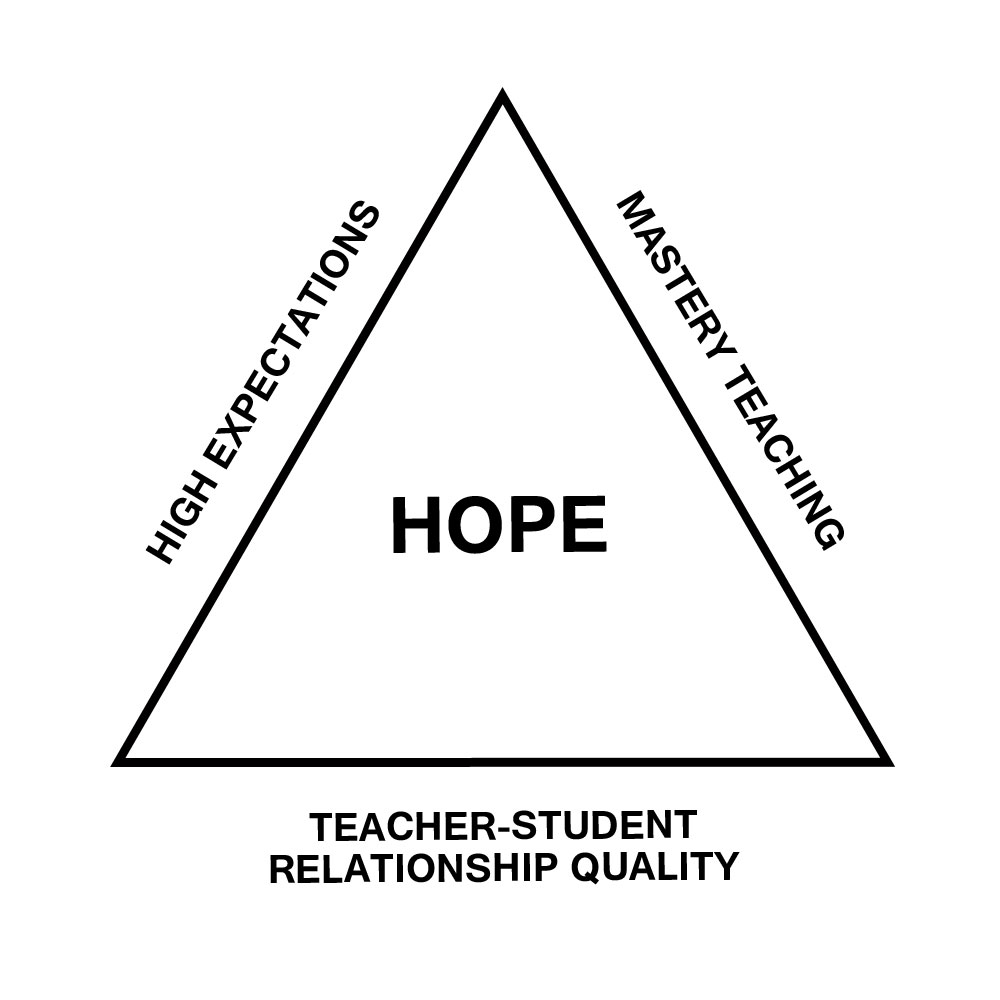

We focused on what we could control. These included:

- Holding high expectations

- Providing the best teaching/learning environment we could

- Fostering positive relationships with our students

We didn’t whine about what we didn’t have or couldn’t control.

I hope the reader sees how the three sides of the triangle work together to produce a school where students experience and believe they are valued and are important to their teacher.

I hope the reader sees how the three sides of the triangle work together to produce a school where students experience and believe they are valued and are important to their teacher.

Will each one be successful? There is no guarantee, of course, but what students are really learning—that can’t be measured by a standardized test—is what responsibility looks like and feels like. That’s true from kindergarten through high school.

It can be done. We did it. Students who live in poverty want to learn and can succeed. The “secret sauce,” so to speak, for my school was our teachers. What worked for us (as I mentioned before, we were fully accredited my last 12 years) was to empower teachers individually, in teams, and as a group.

I called the faculty my Leadership Team and organized the grade levels so they functioned (as much as possible) as self-managed teams. I believe that teachers do their best work when they are part of a team.

My job was to support them, of course—especially with discipline—but from the time I hired each person, my message was clear: You are what makes the difference for these students. There are no magic bullets or formulas, curriculums or strategies. It’s teachers and staff connecting, as much as humanly possible, with each child every day.

Next month in the final installment of “A path to hope” we’ll see what teachers needed from me as principal to be successful—and to maintain and improve their own morale.

Dave Burgess is an independent educational consultant in Richmond, Virginia. He is an adjunct professor for the University of Richmond and a university supervisor for James Madison University. Before retiring as a principal, he was a school counselor. He started his career as a teacher in public schools in Florida and Virginia. Dave can be reached at davidburgess789@gmail.com. The six-part series “A Path to Hope” began in January with the introductory blog “A Path to Hope: Critical Teacher Actions That Transformed a School.”