Martin Miller recently asked an interesting question on a previous blog post of mine – I’d like to take the time to respond to it below. Martin asks:

Thank you, Phil, for sharing this perspective. I struggle personally with the “tyranny” of the mind and thought process and would appreciate more information on this topic. Why is operating from a position of inclusion and respect so difficult for us?

I appreciate that you address this at two levels – your personal struggle with the tyranny of the mind and the broader question about inclusion and respect.

You are not alone: most of us, me included, struggle with our judgmental minds. Buddhists call the “tyranny” of the mind samsara. This is the busy mind, the mind that is always sorting between “for” and “against.” It seems to be in relentless pursuit of “this over that” and — it is exhausting. The Buddhist remedy is meditation, where one learns to quiet the mind. What a relief that can be. And then there is cleaning horse stalls or playing with grandkids to get a little more perspective and balance.

As for “operating from a position of inclusion and respect,” again it’s a problem of being judgmental. When we look at this through the lens of economic class, it appears that judgmentalness arises most easily when we don’t understand the experience of people in other economic classes. Judgments fall hardest on those who don’t have power. In other words, the judgmental attitudes that people in poverty might have about people in middle class or wealth don’t make much impression on the objects of that attitude because the person in poverty has little power and cannot affect the lives of middle class or wealthy people.

But when those from the dominant classes are critical of people in poverty, it makes a difference. The middle class run the institutions, design the programs, and deliver the message.

No one doubts that the middle class mindset and experience has been normalized in our society. The benefits of society naturally bend to serve the normalized group. For example, hand tools and buildings have been designed to benefit right-handed people because right-handedness has been normalized. The “advantages” that right-handed people enjoy are invisible to them and they enjoy the benefits without hating or judging left-handed people.

People who are from generational middle class may have normalized their societal experience to the degree that the benefits and resources they enjoy are invisible to them. They are drawn into thinking that what is “common sense” to them is “common sense” to everyone. They may even ascribe their success in life entirely to their own initiative and not recognize the advantages that being of the dominate class gives them. There are some people who think they hit a triple when they were actually born on third base.

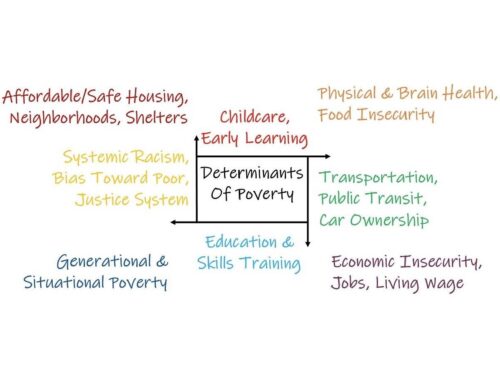

Happily, those of us who are using Bridges concepts for understanding poverty and community well-being are in a position to help people understand economic class and judgmentalness. The tools we use are the mental models of poverty, middle class, and wealth (the environments that arise when there is huge disparity in income and wealth). We understand that hidden rules of class arise from those environments. We learn that poverty is caused by more than the choices of the poor, but by community and political/economic conditions as well. These understandings can lead to a shift in mindset about our own societal experience (if we take ownership of it) and make us open to the experiences and mindsets of others. Add to this the possibility of relationships of mutual respect across class lines and you have the makings of organizational and community change.

At times inclusion and respect may seem to be in short supply; but, at least we have the tools to do something about it. It’s amazing to me how ready people are to move from judgment, disrespect, and polarization to the inclusion found in Bridges, Getting Ahead, and Circles.

-Phil