As a community health worker studying for a master’s degree in human health, I relocated from a small town in East Texas to a college town and was offered a position working for the Children’s Defense Fund of Texas, a child advocacy organization. I was the boots on the ground—I met lower middle class and impoverished families where they were and helped them apply for benefits intended to keep families in poverty afloat.

As a community health worker studying for a master’s degree in human health, I relocated from a small town in East Texas to a college town and was offered a position working for the Children’s Defense Fund of Texas, a child advocacy organization. I was the boots on the ground—I met lower middle class and impoverished families where they were and helped them apply for benefits intended to keep families in poverty afloat.

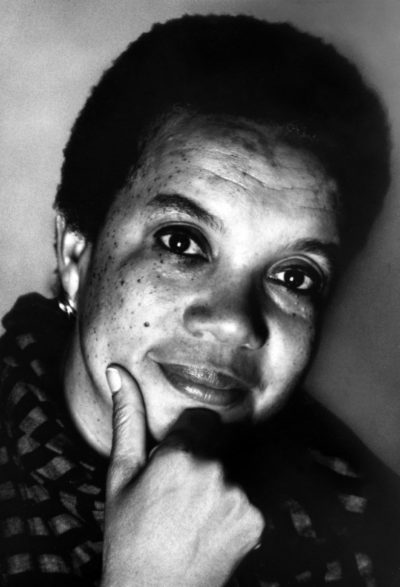

I considered myself just an extension of Texas benefits until I met Dr. Marian Wright Edelman, who graduated from Spelman College and Yale Law School. She started her work in the 1960s, when she was the first Black woman admitted to The Mississippi Bar, and she then directed the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund office in Mississippi. She served as assistant to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. She was not motivated to attend law school until she saw that legal help was greatly needed by many during the civil rights movement. When Dr. King invited President Kennedy to visit the South to view poverty and hunger among children, Marian met one of President Kennedy’s aides, Peter Edelman, and the two eventually married. Dr. King and President Kennedy were both assassinated, but Marian and her husband carried on the cause of equality, especially for children. Marian has greatly influenced the lives of many people, including mine.

I served at an after-school club for underprivileged children and maintained a presence there to assist parents who were picking up children in updating their Medicaid, SNAP, WIC, or CHIP benefits to avoid a lapse in coverage. My job, as a child advocate, was to pinpoint the needs of underserved families in the area and to link them with resources.

The facility called me and asked me to meet with leadership. They heard via rumor that one Hispanic student’s entire family had been deported during school hours and that the young teen came home to an empty house. Weeks had lapsed, and the child was alone in the apartment. I was requested to check out the situation to determine if there was merit to the rumor and ensure that child protective services would not be overburdened. I quickly realized that, within this child’s social class, there are hidden rules that I was not privy to. The child would not find success via a White lady in a business suit who knocked on the door after parents had just been taken away.

But I had an idea. I sat at the beautiful mahogany table and said to myself, I need a priest and a pizza. Most of the local Hispanic population is Catholic, and children are taught to respect Catholic priests. If indeed the child had been home alone for two weeks, groceries were probably about to run out. I called the local Catholic church and convinced the priest to check on the child. The after-school program ordered the priest a pizza to take in hand as a bribe for the child to open the door. It was almost like setting a mousetrap to save the only legal citizen left behind by deported immigrants.

The child opened the door to recognized clergy and was placed with an uncle. The mission would have been a failure if I had not recognized the hidden rules of subcultures and the fear of a child in need. Dr. Payne’s work regarding hidden rules prepared me to help this child in need.