Conversations I have been a part of or overheard:

Conversations I have been a part of or overheard:

“We would like to identify more minority and poor students, but they just don’t qualify. They do not meet our criteria.”

“We did identify several minority and poor students, but they dropped out of the program within six weeks. We just cannot keep them in.”

“We have worked so hard to get more high school students in the AP program; however, they simply will not participate. They say privately that they do not want to be made fun of by their friends.”

If you have heard these comments or made them yourself, you are not alone. There are two separate issues here: one is identification and the other is keeping students in the program. Let’s look at the first issue: identification.

IDENTIFICATION

There is a large misunderstanding between being gifted and being an achiever or having an advantaged background. Many identification approaches confuse the two. If the two standard deviation rule – i.e. 95% of the population falls within two standard deviations of the norm – is followed, then 95% of the population falls between a 70 and 130 IQ. The 2.5% of the population that falls above 130 is considered “gifted.” However, that population can go from a 130 IQ to unmeasurable levels. There is actually a greater difference in that 2.5% of the continuum than there is in the whole of the 95%. So testing alone cannot measure “giftedness.” Therefore, typically it is measured in a set of characteristics.

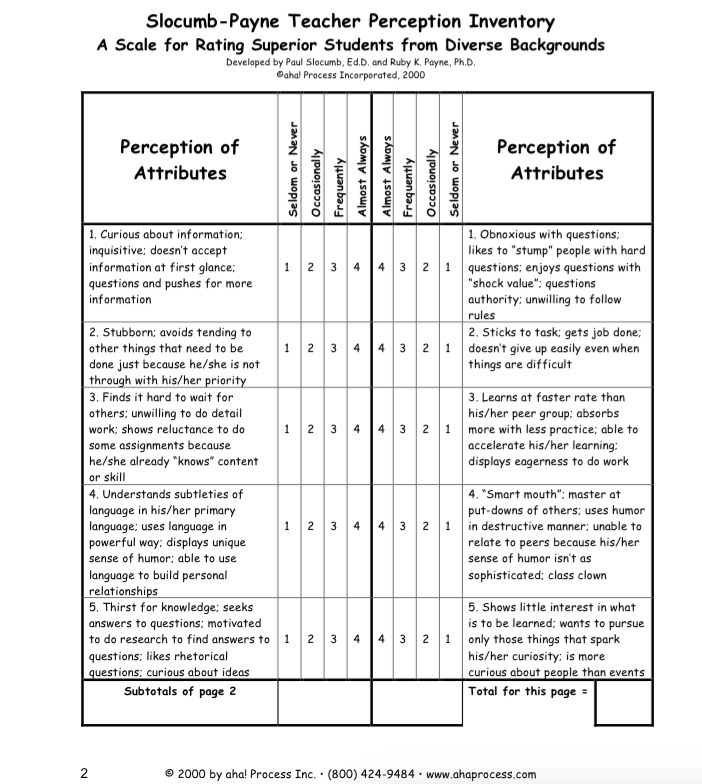

What are these characteristics? The chart below, taken from the book, Removing the Mask: How to Identify and Develop Giftedness in Students from Poverty, has them. Most programs only measure the positive side of these characteristics and not the negative side. Giftedness is giftedness – be it in the positive or negative form – so many gifted students are not identified because they only measure the positive side.

Other identification mechanisms almost always use:

- Test scores (heavy emphasis on vocabulary and acquired knowledge)

- Teacher recommendation (the research is very inaccurate; peer recommendation tends to be more accurate – see identification items in Removing the Mask)

- Grades (very dependent on the student’s external resources)

KEEPING STUDENTS IN THE PROGRAM

There are basically four reasons why students do not stay in the program:

- There is a lot more work but not more interesting work

- The student does not have the external resources in their household to do the extra work

- Their friends and often parents are not supportive and make fun of them

- There is no one in the class that looks like them

So how do you address these three major issues?

Extra work but not interesting work

One of the most interesting discussions about intelligence is whether or not it is related to the speed of learning and processing information. Often tests are timed, which is related to this concept of speed (i.e. how fast you can do/learn something). So in gifted education, many times a lot more work is given, but it is busy work rather than interesting content.

What will make work interesting for gifted students is work that requires more thought. For example, rather than reading two stories and answering the questions on them, the assignment would be: Read these two stories. In this first one, the author makes you love the main character. In the second story, the author makes you hate the main character. How do the authors do this? Compare and contrast the ways in which the author does that.

External resources are not available

Many, many projects in gifted education programs require the involvement and resources of a parent. If the parent is working two jobs or the student is the support system for the household, the demands of the gifted program are simply too intense. So the student drops out.

So what do you do about that? You make certain that all project work is done in the classroom or that everything required for the project is provided. Why should we give credit and grades to work that a parent has done?

Friends and family are not supportive

“Now you are one of them.” This comment is not uncommon in high poverty households when a student does well in school. A common fear that exists among adults in high poverty households is that, when you get old, you will not have physical safety. So you like your children close. (Often when children get educated, they leave.)

To get more students involved at the secondary level in AP and gifted classes:

- Have them be with a “buddy,” another student who has similar external realities so they can take “the heat” together

- Have them identify who will support them getting educated and who will not support them; help them make a plan for the non-support

- Have students like them who have successfully completed the course to speak on DVD, Youtube, video, mp4 files about the challenges and how they dealt with them

There is no one else that looks like me

An African American friend of mine told me that her son refused to learn because “nobody in the books looked like him.” Belonging is a huge issue in learning. All learning is double coded – emotionally by relationships and cognitively. All emotional well-being is based upon safety and belonging.

Gifted programs tend to be autonomous and competitive. In other words, you are on your own, and you will compete for grades. Many students from high poverty and minority households simply will not participate in that kind of learning. They will participate if it is relational and competitive. In other words, I am part of a group that competes with other groups. It is important to use books, materials, photos with individuals who look like your students. It is about belonging.

CONCLUSION

For gifted programs to be truly effective, it is important to have many different voices at the table.

Ruby K. Payne, Ph.D. is the founder of aha! Process and an author, speaker, publisher, and career educator. Recognized internationally for A Framework for Understanding Poverty, her foundational book and workshop, Dr. Ruby Payne has helped students and adults of all economic backgrounds achieve academic, professional, and personal success.