@PhilDeVol

@PhilDeVol

Summary:

People completing Getting Ahead in a Just-Gettin’-By World (GA) frequently enter a work world of instability and disengagement. Instability is associated with flex hours, temporary work, outsourced contractual work, and part-time jobs instead of full-time work. Disengagement comes from being expendable to the employer; not having a meaningful role in the company and not belonging.

I have been learning about instability in the workplace from GA graduates entering the workforce and from studies done in the U.S., Western Europe, and Australia where Getting Ahead is being introduced. The growing number of people who have unpredictable, insecure employment is not likely to be engaged at work or in the community. This precarious way of life is reaching up from entry level, low– jobs into what were once solid, middle class jobs.

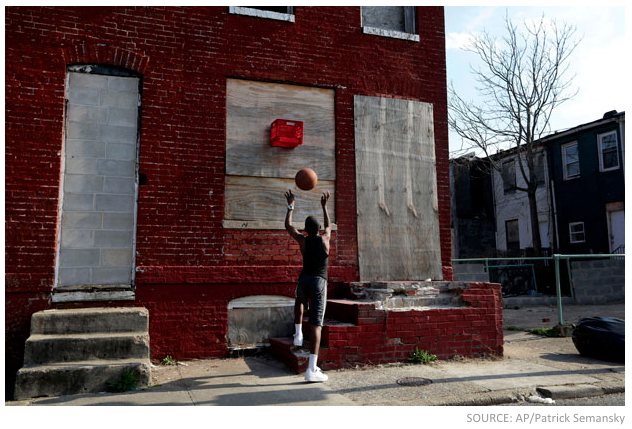

I am concerned for GA grads who are joining the workforce for perhaps the first time. While they struggle to get and keep a job, they may not be aware that they are heading straight into the brick wall that the working class and middle class have already hit – the wall of stagnant wages despite higher productivity, higher living costs, and jobs that don’t offer security. Put another way, Bridges communities are trying to help people get out of poverty at a time when the working class is slipping into situational poverty and the middle class is becoming destabilized.

Details:

Many GA graduates are joining the workforce. In studies done as long ago as 2004, full-time employment for low-wage health  care workers in Youngstown, Ohio went from 29% to 76%, and, in a 2014 study of GA groups in Akron, Ohio, unemployment dropped from 83% to 57% and full time work (40 hours/week) went from 1 percent to 16 percent.

care workers in Youngstown, Ohio went from 29% to 76%, and, in a 2014 study of GA groups in Akron, Ohio, unemployment dropped from 83% to 57% and full time work (40 hours/week) went from 1 percent to 16 percent.

But, what is employment like? What are GA grads facing when they go to work? Recent studies have a lot to say about two issues: stability and engagement. These two factors have immediate and future implications for GA grads entering the workforce.

First, instability is a key feature of poverty. It appears in personal choices, family dynamics, and neighborhood conditions. It is ever-present in daily life. Transportation, childcare, elderly care, housing, medication, health, and income are all likely to fall apart in an under-resourced world. This instability drives people into the tyranny of the moment where all problems must be dealt with immediately. (Source: Scarcity, Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir)

People entering the workforce from poverty have to overcome the tyranny of the moment to make it to work every day. It would be reasonable for them to assume that getting and holding a job would finally lead to stability and security.

The ideal job provides full-time employment; a reliable income, earned sick leave, paid holidays, earned vacation days, benefits, pensions, and a ladder to climb to higher positions. The workplace is where you belong and where your opinions and contributions count. The workplace is where you can get ahead and secure your future.

But there are fewer ideal jobs now and a whole lot more instability. Sadly, it appears that work can actually contribute to instability. Downward pressure on wages is linked to the growing number of survival jobs (e.g. odd-jobs, temporary work, part-time employment, outsourced contractual work, and flex hour shifts) makes it difficult to schedule the second job that’s needed to make ends meet. In one study, 61 percent of Americans say their family’s income is falling behind the cost of living, compared to 29 percent who feel they are staying even and 8 percent who feel they are getting ahead.

GA graduates know just how hard life can be when instability rules. In Getting Ahead, they do a personal stability assessment and hold themselves accountable for becoming more stable; some use a free mobile app to track their stability. But individuals cannot be accountable for employment conditions that create instability.

Disengagement is tied to instability, particularly in the types of jobs that don’t attempt to engage employees or treat them like ‘real’ employees. For example, a report by the American Association of University Professors showed that 76.4 percent of US faculty across all institutional types are adjunct professors – in other words, contingent labor. They have no guarantee of a steady income, often have to take second jobs, and sometimes have to commute between two campuses. As a consequence, they cannot get a loan to buy a house and may not be able to afford childcare. They, like fast food workers and part-time workers in factories and big box stores, are living a precarious life.

These forms of instability mean that families don’t get rooted in the community. Moving from job to job and house to house might mean that children can’t join in sports, and parents can’t join the PTA or participate in other community activities that make up the heart of a democracy. As a result, everyone suffers: the disengaged worker, local businesses on main street, and the employer. After all, engaged workers are productive, creative, influential, and proud ambassadors of their employer in the community.

Unfortunately, disengagement is reaching from the unstable jobs we’ve been discussing into full-time jobs. A recent Gallup Inc. study found that 70 percent of workers are not engaged and are emotionally disconnected from their workplaces and 17 percent were actively disengaged. This, of course, is not good for business or the community, to say nothing of the impact on individuals entering the workforce.

In the face of all these negative trends, we have GA graduates entering an achievement-based world from a relationship-based world. They come to work with the tools to build relationships of mutual respect and are eager to navigate the world of achievement. They know the difference between bonding and bridging social capital and the hidden rules of class. They see themselves as problem-solvers and want to contribute to solutions in the workplace and the community.

These two international trends, workplace instability and disengagement, are not likely to turn around anytime soon. And these trends are going to be a problem for GA grads who join the workforce as well as community leaders who want to build prosperous sustainable communities.

So, what might Bridges Out of Poverty initiatives do about these trends in the workplace? Here are some ideas:

So, what might Bridges Out of Poverty initiatives do about these trends in the workplace? Here are some ideas:

- Reaffirm the commitment to provide long-term support for people climbing out of poverty.

- Listen to what GA graduates say about the workplace barriers they encounter and take action at the individual, institutional, community and policy levels to overcome those barriers.

- Use stability and engagement/social coherence factors to determine employment policies. Collect and evaluate data on stability and engagement factors at the individual, institutional and community levels. Individual data collection and reports are available from providers of Getting Ahead evaluations.

- Make changes in employment practices and then share best practices with other employers. An example would be the Small Dollar Loan program provided by the Bridges initiative in Lucas County, Ohio.

- Engage Getting Ahead grads as co-creators of healthy and prosperous communities. They can do more than go to work; they can help build communities.

Please consider this an invitation to join the conversation by writing and tweeting to #workforcestability, @ahaGAnetwork, @PhilDeVol and @ahaBridges.

Phil DeVol is co-author of Bridges Out of Poverty: Strategies for Professionals and Communities and author of Getting Ahead in a Just-Gettin’-by-World.