Day 1 of our Tactical Communication training begins, and the officers arrive with questions. We are at the Martin Luther KingEvent Center in Muskogee, Oklahoma, a beautiful facility with first-rate services.

“Is this about how to talk to terrorists?”

“Are we learning how to talk during a hostage crisis or critical incident?”

Disappointment shows briefly when the answer is “no” and they find out this is about something else entirely.

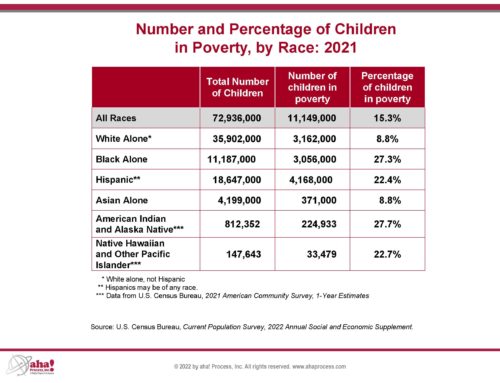

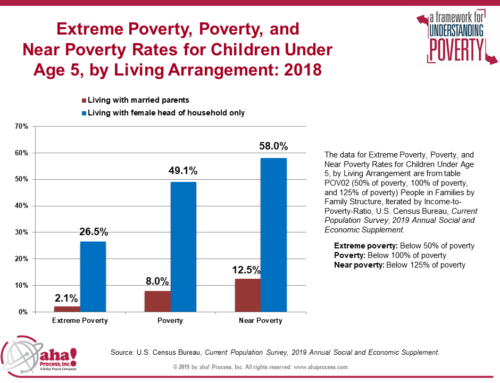

The discussion starts, and the officers are polite but not engaged. We talk about the basics of poverty and move to hidden rules. I tell them that people in generational poverty are all about survival and that living for the moment rules their day. The interest is there, but the lightbulbs are not lighting up.

Then we start to discuss hidden rules of law enforcement and the policing profession, the challenges of what is happening today in our society. Now they are engaged, especially when we talk about the fact that you have to be careful, that policing is a dangerous gig. I ask the question I’ve asked a hundred times to cops: “What is a good day for a cop?”

For the good people of any community, the answer is simple: A good day for the cops is when they get to arrest a bad guy—a murderer or a robber, for example. A good day is when they make a difference. A good day for any cop is when the cops get their man, help someone, save someone. That’s the community’s perception of a good day for the police.

But the answer is significantly different for those in law enforcement and has been for quite some time. What is a good day for a cop?

“Going home safe. I didn’t get hurt, and I didn’t have to hurt anyone.”

Over the last several decades we have taught police officers how to stay safer, and the results have been impressive. The number of on-duty deaths for law enforcement due to violent attacks has declined regularly for many years. Training people to be aware, to be hypervigilant, has paid dividends. We define hypervigilance as the necessary manner of viewing the world from a threat–based perspective, having the mindset to see the events unfolding as potentially hazardous. The idea is that I know not everything is a threat, but if I treat everything as a threat, when the real threat comes, I will be ready for it!

Now the cops in the room are connected, engaged. Now I give it to them.

“You know, we talked about the hidden rules in poverty and how the mindset in poverty is all about survival. And now you are telling me that your mindset is also about survival. It seems to me you have a lot more in common with the people you are policing than you might think. You are both just trying to make it through the day, trying to survive.”

They begin to nod, slowly, some imperceptibly, but it is there … the aha! moment. And now we can start to build some bridges.

Gary Rudick is a 35-year veteran of law enforcement in Oklahoma, serving the citizens of the state as a patrol officer, supervisor and chief of police. He has a Master’s in Criminal Justice and is a graduate of the FBI National Academy, Session 242. He led one police agency to receive the International Association of Chiefs of Police Civil Rights Award, and the same agency was recognized for achieving state accreditation. Read more about Gary.