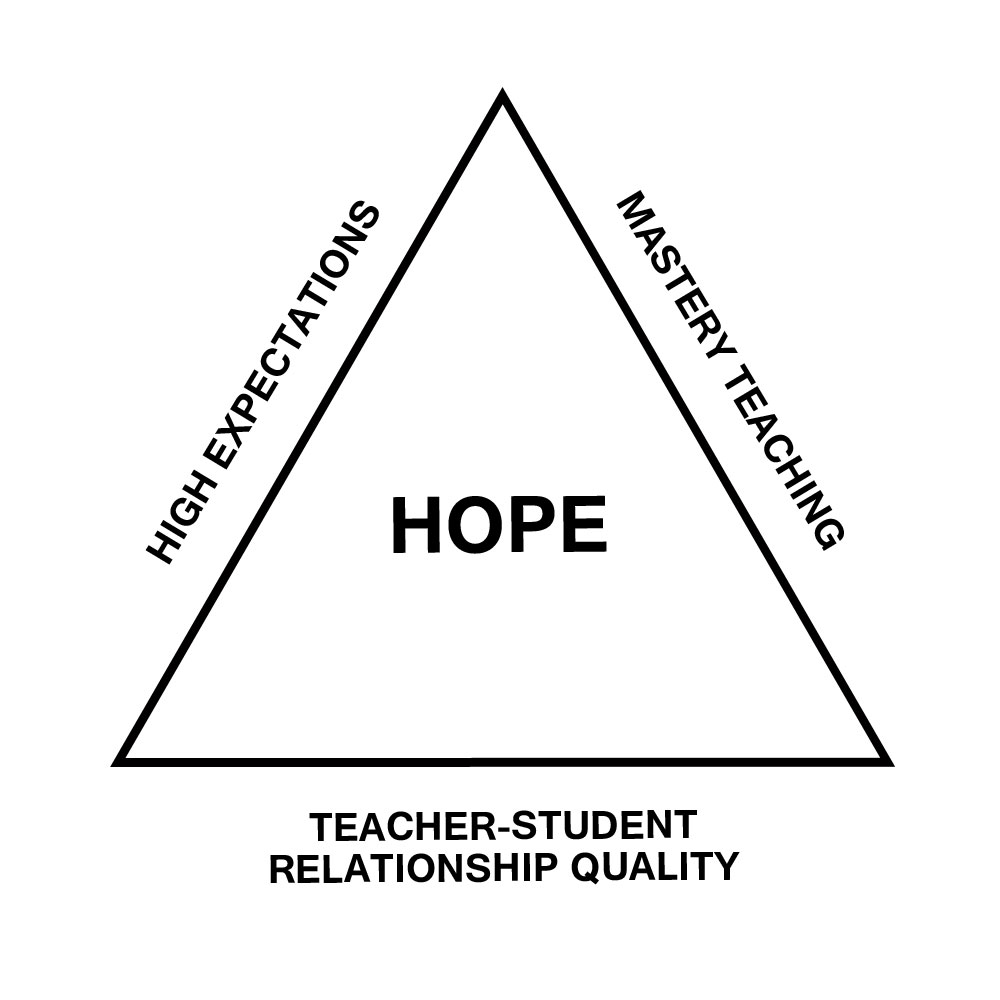

Last month we focused on mastery teaching. This month we will learn what is the key to helping students make the transition from poverty to living into the possibility of a hopeful future.

Teacher-student relationship quality (TSRQ) lay at the heart of what we did in our Virginia school to succeed.

Teacher-student relationship quality (TSRQ) lay at the heart of what we did in our Virginia school to succeed.

In their seminal 2011 book, Creating the Opportunity to Learn, Boykin and Noguera point out this is the single most referenced factor in the professional literature regarding building engagement and success with at-risk students.

We didn’t call it TSRQ when we chose what to do with our students. But as I think back, many of our initiatives fell under this umbrella for building success. Here are a few elements of what we did.

Teach communication skills: I worked with our school counselor to ensure that our students had ample opportunities to engage with each other. In classroom lessons, students were taught communication skills and how those skills relate to problem-solving with people.

Solving problems means learning three things: that others have feelings, just as you do; that others don’t necessarily think the same as you; and especially that there are ways to arrive at “win/win” answers to communication issues among people. Stereotypical and prejudiced thinking has no place in valuing each other.

Another exciting thing our counselor did was conduct peer-facilitation groups, as I did when I was a school counselor. I used the Myrick and Bowman program Becoming a Friendly Helper as a leadership-skills program for older students. This program taught four basic communication skills of active listening—how to listen, ask open-ended questions, clarify and summarize, and make feeling-focused responses.

Our counselor used this same program to encourage children to have empathy for others; to train children who could act as facilitators to work with others to solve communication issues at recess or in the classroom; and to be role models who could relate to younger children on developmental concerns.

A neat twist on this is to take children who have obvious leadership skills (though often shown in negative ways) and work with them in small groups to learn communication skills, develop empathy for others, and take pride in themselves. They blossom!

Conduct class meetings: Along with what the counselor taught in the classrooms, our teachers conducted some version of class meetings—more formal in the upper grades, shorter time-framed discussions with younger children (morning meetings).

But always, the emphasis was doing the right thing, taking responsibility for what you do, everyone is important, and we work together. Those principles relate to bullying, which has at its roots disrespect for others and going along (with a bully) to get along. Choosing to be a bully is a choice, and deciding whether to support that bully is a choice as well.

Teach goal-setting: Children from poverty are rarely taught how to set goals and how to pursue them. In fact, much of one’s living in poverty involves magical thinking, as a movie of a few years ago showed: “Waiting for Superman.” One of the individuals interviewed—now a successful educational leader—said that when he was a boy he couldn’t understand where Superman was and, with all the problems he saw where he lived, what was Superman waiting for?

So much of the academic curriculum, as well as what class meetings and counselor visits address, can be tied into learning how to set goals—both short-term and long-term.

In the elementary school, children related well, for example, to setting a goal to learn their math multiplication tables in a given time period, and they could see their progress to achieving the goal through a car-race poster showing students’ cars as they “race” toward the finish.

Other examples would include earning stars for most books read, passing the state physical-education tests, and so on. In other words, don’t take it for granted; make it a specific goal and monitor progress toward that goal.

Bottom line? One must actually set a goal, pursue it, and evaluate success or failure in order to internalize what it means. Most students from poverty have little experience in setting goals. They must be given opportunities to learn from planned efforts to succeed.

Teach with quality in mind: In 1990 Dr. William Glasser, a leader in applying the business concept of total quality management (TQM) to schools, had a novel idea in The Quality School: Managing Students Without Coercion.

According to Glasser, achieving quality results, just like one’s motivations, starts within each person. Why not teach students the concept of quality and allow them to rate their own efforts? If you think you did a quality job on a given assignment, put a Q at the top. If not, talk with the teacher about it. This was especially helpful during post-writing conferences in teaching direct writing in grades 4 and 5.

According to Glasser, achieving quality results, just like one’s motivations, starts within each person. Why not teach students the concept of quality and allow them to rate their own efforts? If you think you did a quality job on a given assignment, put a Q at the top. If not, talk with the teacher about it. This was especially helpful during post-writing conferences in teaching direct writing in grades 4 and 5.

Additionally, we celebrated “Quality Month” each January. We designated each week in the month: Responsibility Week, Respect Week, Hard-Work Week, and Quality Week. As Glasser says, “If you want quality, you have to talk about it.”

Each January quality was the context for instruction, and we had speakers/role models/guest readers come to school to demonstrate to the students what quality looks like in the real world. We invited successful parents and workers to read to our kids because “Leaders Are Readers.”

I found that the concept of quality is one students can get into (who wants a low-quality Xbox? a low-quality dentist?), and it’s especially helpful in teaching how to define a goal worth pursuing.

Engage and move: Let me be clear! The lecture method of instruction is the antithesis of what students from poverty need to be successful. It barely works for most students; it’s a disaster for those from poverty. Why?

What I’ve said previously in several places and in several ways is the need for students to be engaged: both minds and bodies. High expectations and questioning—coupled with mastery teaching, along with small-group discussion and partner-teaching—are critical to engaging the mind and body.

Further, such instruction and interaction make learning a positive social endeavor. Learning should be fun!

Organize Career Day/Week: Finally, don’t overlook the importance of Career Day and Career Week for students from poverty. This is a chance to match up kids with successful adults who are ready to share what they do and how they came to do it. There are many ways to follow up with “career” activities to make this learning relevant to students.

Career Days are nice to have in middle-class schools; they are a necessity in schools with a high-poverty population.

All the activities described above are intended to build and deepen high-quality relationships between teachers and students. And students from poverty often benefit the most from these relationships.

Later this month we’ll discuss how to curb misbehavior and build self-discipline in students. We’ll see what worked for us, as well as what we didn’t do (and why).

Dave Burgess is an independent educational consultant in Richmond, Virginia. He is an adjunct professor for the University of Richmond and a university supervisor for James Madison University. Before retiring as a principal, he was a school counselor. He started his career as a teacher in public schools in Florida and Virginia. Dave can be reached at davidburgess789@gmail.com. The six-part series “A Path to Hope” began in January with the introductory blog “A path to hope: Critical Teacher Actions That Transformed a School.”